Lesson plans are a waste of time. Lesson plans take too long to write. Inexperienced teachers find lesson planning too hard and too time consuming. Even experienced teachers can find lesson planning a time-consuming process or feel like it’s a waste of time. Heard or thought this before?

Why then do teachers find it so hard to plan lessons? Surely you don’t want to spend the whole night awake staring at a coursebook, a document a student gave you, an authentic article or a perfect podacst that you’re dying to use with your groups. The answer may not be in the process itself, but the way you approach the process.

Lots has been said about the merits of planning lessons and the advantages of not planning classes. This is not the a point I want to address in this post- I’ll leave that to the pros here

Anthony Gaughan and Chia Suan Chong’s discussion

Materials are designed for learners

While the teachers book might give you a ‘final product’ style lesson plan, the students book is most often designed to give the user (aka the student) the smoothest journey through the course. I’ve only seen a few attempts to integrate lesson plan ideas for the teacher in students books, most successfully I think in the latest edition of In-company Upper Intermediate.

At the same time, some materials can be harder to unpack. What I mean by this is that the framework or methodological foundation for the coursebook is sometimes not clear to the untrained eye. If you’re trying to plan your lesson according to either your own framework or second-guess the coursebook’s framework, you might find yourself spending too much time on the plan before you’ve even come up with an idea.

Advice: don’t try and second-guess materials while lesson planning. If you have a new coursebook, get to know it and spot the patterns by looking through the whole book.

Teachers are full of ideas

If you’re like me, you have too many ideas when you plan lessons. Your brain becomes overloaded with new ideas and interesting warmers, adaptations or extra activities you know that could fit in. The result is a lots of content and no structure, or losing one idea because another great one has come along

That’s because your mind is brainstorming but the “I must plan my lesson” structure is inhibiting your creativity. At the risk of sounding cheesy, teachers are massively creative and take pride in their creativity. The process is hindering you. Break free and channel your creativity.

Lesson planning is brainstorming

It is. While you look at the materials you want to use, pick up a packet of sticky notes and write down ideas, one per note and stick them to the table. At this stage it’s not important whether it’s a warmer, pre-task, post-task, freer practice, controlled practice, language presentation, lesson review, learning checking, content checking, meaning checking or conversation focused idea, it’s an idea. Please do not evaluate any of your ideas in this section.

You should follow this process for about 5-10 minutes. The table could have anywhere between 5 and 20 ideas on it. Close the coursebook, put the materials down or put the podcast away.

by jakecaptive under creative commons

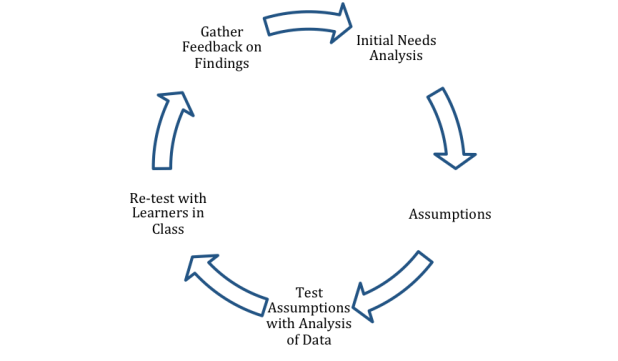

Go divergent, evaluate, go convergent

Now you’ve just done something very divergent for your mind. Your brain is probably feeling tested and happy. It’s important to sort these ideas now.

Idea 1:

Put the ideas in columns. Give each column a title. This could be something like “warmer” or something like “1-1 ideas” or “group ideas”.

Idea 2:

Use a traditional lesson structure “warmer” –> “language presentation” –> “controlled practice” –> “freer practice” or whichever lesson framework you are most comfortable using.

Idea 3

If you have many similar ideas, use a descending list for suitability for the class.

Evaluating your ideas, you will be in a better position to discard some ideas. Don’t worry. You can keep them for future lessons if you really like them. What’s important is that you’ve caught all your creative goodness and put it into a structure.

Now you’re ready to converge. Get a page of white A4 paper and add your sticky notes to the paper in one column and the usual comments for your lesson plan in the other column.

What to do with the rest of the ideas? They don’t need to be lost – take a picture of them or collect them in an ideas book for future use.

When I started planning my lessons in this way, I immediately found the process more proactive and more gratifying . My students also noticed the difference the jump in creativity!

Advantages are:

- By not introducing a framework too early, you don’t inhibit your creative ideas

- Brainstorming allows you to explore many possibilities without constraints. You let your creativity flow.

- Sorting and distilling helps your ideas fit into a framework

- Closing the book and then going back to it treats our materials as stimuli for the creative process of lesson planning; not the cause of the creative drought.

If you try it out, take a picture of the divergent stage and final lesson plan and share your experience with me in the comments section.